The \(k\)-server problem is one of the most important and most well-studied problems in the field of online algorithms. The goal of this blog is to describe the problem to you and give you some flavor of the underlying techniques used in the recent breakthrough by Sebastien Bubeck, Michael Cohen, James Lee, Aleksander Madry and me. (Note that three of them are members of ADSI!) For a detailed blog with proofs, please see here.

Background

In this problem, we control the movement of a set of \(k\) servers on a fixed metric space of \(n\) vertices. In each iteration, we are given a request \(r\). If there is no server at that location, we must choose a server, move it there and pay the movement cost of this server. Our goal is to minimize the total distance of all servers’ moves. This problem is very general and is originally proposed to model problems related to cache management.

We call an algorithm \(f(k,n)\)-competitive if for any request sequence, its total movement is at most \(f(k,n)\cdot\text{OPT}\) where \(\text{OPT}\) is the optimal movement cost if the whole request sequence is given in the beginning. A priori, it is unclear that any competitive algorithm exists because we are comparing against a powerful algorithm that knows the whole request sequence and is free to make any moves.

To illustrate the learning aspect, consider a \(2\)-server problem on a graph with 3 vertices \(\{a_{1},a_{2},b\}\). Suppose that \(d(a_{1},a_{2})=1\), \(d(a_{i},b)=2017\) for \(i=1,2\) and the request is

\[a_{1},b,a_{2},b,a_{1},b,a_{2},b,\cdots\cdots.\]Since \(a_{i}\) and \(b\) are so far away, the optimal strategy for this sequence is to put a server on \(a_{i}\) and a server on \(b\). However, if \(b\) appears less frequently than once per \(2017\) iterations, a better strategy would put both servers on \(a_{i}\) most of the time. Therefore, any memoryless algorithm is not competitive and that we indeed need to learn something.

One main focus for the \(k\)-server problem is to achieve competitive ratio independent of \(n\) because of the common case \(k\ll n\). Two of the major open problems is to find a \(k\)-competitive deterministic algorithm and a \(O(\log k)\)-competitive randomized algorithm for the \(k\)-server problem. For the deterministic problem, Koutsoupias and Papadimitriou gave a deterministic algorithm that achieves a competitive ratio of \(2k-1\) on any metric space. However, there has not been too much progress on the randomize problem. In particular, there is no \(o(k)\) competitive algorithm except for simple classes of graphs such as weighted complete graphs. Due to its importance and the gap between the lower and upper bound, the following “easier” problem had been a major target of the field. And in my opinion, this was the most important conjecture in online algorithms.

(Weak randomized \(k\)-server conjecture) There is a randomized algorithm for the \(k\)-server problem on any graph with competitive ratio \(\log^{O(1)}(k)\).

The previous best competitive ratio is \(O(\log^{3}(n)\log^{2}(k))\) (by Bansal, Buchbinder, Naor and Madry in 2011). In our paper, we give an algorithm with competitive ratio \(O(\log^{2}(k))\) on hierarchically separated trees (HST, a much larger classes of graphs) and as a corollary \(O(\log^{2}(k)\log(n))\) on general graph. Soon after our paper, James Lee developed upon our paper and gave an algorithm with competitive ratio \(O(\log^{6}(k))\), finally resolving the weak randomized \(k\)-server conjecture!

Online Learning and Mirror Descent

Our algorithm is based on mirror descent with a multiscale entropy. So, let me describe an online learning problem and the mirror descent algorithm for it.

In this problem, we are given a convex set \(K\). In the \(k^{th}\) iteration, we select a vector \(x^{(k)}\in K\), then the adversary selects a vector \(v^{(k)}\) in \(K\) and we receive a loss \(v^{(k)\top}x^{(k)}\) for that iteration. Our goal is to minimize the regret (the difference between your loss and the loss of the optimal fixed strategy)

\[\sum_{k=1}^{T}v^{(k)\top}x^{(k)}-\min_{x\in K}\sum_{k=1}^{T}v^{(k)\top}x.\]This problem can be solved by mirror descent:

\[x^{(k+1)}=\text{argmin}_{x\in K}\eta\cdot v^{(k)\top}x^{(k)}+D_{\Phi}(x;x^{(k)})\]where \(\eta\) is the step size, \(\Phi\) is a convex function on \(K\) called mirror map and the Bregman divergence associated to \(\Phi\) defined by

\[D_{\Phi}(y;x):=\Phi(y)-\Phi(x)-\nabla\Phi(x)^{\top}(y-x).\]When \(x\) is very close to \(y\), \(D_{\Phi}(y;x)\sim(y-x)^{\top}\nabla^{2}\Phi(x)(y-x)\) and hence mirror descent is simply moving \(x\) towards \(-v\) direction while making sure the point is in \(K\) and it is not too far from the previous point in \(\nabla^{2}\Phi(x)\) norm.

For me, a general wisdom, when facing a new learning problem, is to check if mirror descent or some of its variant is good. See my favorite example here.

Weighted Complete Graph

Unfortunately, applying mirror descent to the \(k\)-server problem is not as easy as picking a good mirror map as I wished. Let me first describe the algorithm for the complete graphs with the metric of the form \(d(i,j)=\omega_{i}+\omega_{j}\). For this and many other graphs, it is known how to turn a fractional solution \(x(t)\in\mathbb{R}^{n}\) that is feasible

\[0\leq x_{i}(t)\leq1 \text{ and } \sum x_{i}(t)=k\]to an integral solution \(\widetilde{x}\in\{0,1\}^{n}\) with the movement cost bounded by \(O(1)\cdot\int_{0}^{T}\omega_{i}\left|\frac{dx_{i}}{dt}\right|dt\) (a natural continuous definition of movement cost). Therefore, it suffices to propose a fractional algorithm (the first prerequisite for applying mirror descent).

Our algorithm is motivated by the \(O(\log k)\) competitive-algorithm by Bansal, Buchbinder and Naor in 2007. To make its relation to mirror descent clear, I describe our process here as a discrete process with an infinitesimally small step size \(\eta\). Instead of working on the fractional server \(x(t)\), our algorithm is defined on the fractional anti-server \(y(t):=1-x(t)\):

- Let \(K=\{0\leq y\leq1,\sum_{i=1}^{n} y_{i}=n-k\}\).

- Let \(\Phi(y)=\sum_{i=1}^{n}\omega_{i}(y_{i}+\frac{1}{2k})\log(y_{i}+\frac{1}{2k})\).

- When the request for the vertex \(\ell\) arrives

- While \(y_{\ell}^{(k)}>0\).

- \(y^{(k+1)}=\text{argmin}_{y\in K}\eta\cdot e_{\ell}^{\top}y+D_{\Phi}(y;y^{(k)})\) where \(e_{\ell}\) is the coordinate vector at \(\ell\).

- \(k \leftarrow k+1\).

- While \(y_{\ell}^{(k)}>0\).

In short, when the request arrives at \(\ell\), we run the mirror descent with the cost \(e_{\ell}\) until all anti-mass \(y\) leaves the coordinate \(\ell\).

The reason of using \(e_{\ell}\) is to put a “cost” at coordinate \(\ell\) that forces all anti-mass at \(\ell\) leaves (equivalently, attracting servers to move to \(\ell\)). Since \(K\) is a simplex, the standard choice of the mirror map is \(\sum_{i}\omega_{i}y_{i}\log y_{i}\). However, this mirror map is not suitable because its gradient \((1+\log y_{i})_{i}\) blows up on the boundary. Following the idea in (BBN07), we shift all variables by \(\Theta(1/k)\) in the mirror map.

Since the step size is infinitesimally small,

\[D_{\Phi}(y;y^{(k)}) = (y-y^{(k)})^{\top}\nabla^{2}\Phi(y^{(k)})(y-y^{(k)}) =\sum_{i}\frac{\omega_{i}}{y_{i}^{(k)}+\frac{1}{2k}}(y-y^{(k)})^{2}.\]Using this, one can show that the algorithm is moving the anti-mass \(y\) from coordinate \(\ell\) to coordinate \(i\) with a rate proportionally to \((y_{i}^{(k)}+\frac{1}{2k})/\omega_{i}\). Namely, the algorithm tends to move the server from vertices with smaller weight and less server mass to the request. One can show this algorithm has a \(O(\log k)\) competitive ratio.

Hierarchically Separated Tree

In general, it suffices to solve the \(k\)-server problem on HST metrics (BBNM11). This reduction would cost a \(\log{n}\) factor in the competitive ratio. Given a tree \(T=(V,E)\) with vertex weights \(\omega>0\), we define the metric on the leaf \(\mathcal{L}\) by \(d_{\omega}(\ell,\ell')=\omega_{\text{lca}(\ell,\ell')}\) where \(\text{lca}(\ell,\ell')\) is the least common ancestor of \(\ell\) and \(\ell'\). We call this tree is a HST if \(\omega_{v}\leq\omega_{u}/6\) whenever \(v\) is a child of \(u\) and we call the metric space \((\mathcal{L},d_{\omega})\) a HST metric.

Two main questions to be decided are:

- How do we represent the solution?

- What is the mirror map we use?

One natural choose is to represent anti-mass \(y\) using

\[B:=\{y\in[0,1]^{V}:\ y_{r}=n-k\text{ and } y_{u}=\sum_{p(v)=u}y_{v}\}\]where \(r\) is the root of the tree and \(p(v)\) is the parent of \(v\). The main issue of this representation is that it cannot distinguish between the case we need exactly 1 server in a subtree or we need 2 servers with 50% probability. Another small issue is that some constraint is never active. Using the fact that the algorithm is always moving servers to the request until \(y_{\ell}=0\), one can show that \(1\geq y\geq0\) and \(y_{u} \geq \sum_{p(v)=u}y_{v}\) are never active.

Fixing these issues, we have a new representation

\[K:=\{y:\ y_{i,r}=1_{i>k}, \qquad \qquad \qquad \qquad \\ \qquad \qquad \sum_{i\leq\left|S\right|}x_{u,i}\leq\sum_{(v,j)\in S}x_{v,j} \ \forall S \}.\]where \(S\) are sets of pairs \((v,j)\) with \(p(v)=u\). The first set of constraints ensures that there are only \(k\) servers in total and the second set of constraints ensures that the number of servers in the children of a vertex \(u\) is at most the number of server at \(u\).

The mirror map we pick is a generalization of the mirror map on a simplex

\[\Phi(y):=\sum_{u\in V}\omega_{u}\sum_{i\geq1}(y_{u,i}+\delta)\log(y_{u,i}+\delta)\]where the shift \(\delta=\frac{1}{2017k}\).

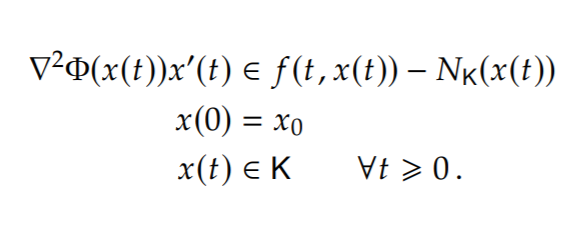

Except for some technical issues, our algorithm for HST is the same as the algorithm described for the complete graph except this new \(K\) and mirror map \(\Phi\).

Open Problems

The proof of the classical mirror descent is clean, short and optimal. Unfortunately, our proof is slightly longer (i.e. few pages) and the bound we get for HST does not sound optimal. We hoped to get the ultimate algorithm for \(k\)-server at least for HST, however, our algorithm seems to not be the one from the BOOK. So, what is the algorithm from the BOOK for the \(k\)-server problem (at least for HST)?

On the other hand, it is interesting to see if HST is necessary for an \(\log^{O(1)}k\)-competitive algorithm on general graphs (or for a path). Maybe I am too naive on this and HST is indeed the right tool?